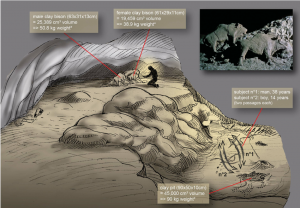

The bison stood next to each other, built from the cave walls, leaning against a small boulder in the darkness.

While they are 18 feet twenty-four inches long, they are beautifully constructed and durability is remarkable.

The bison remained alone for thousands of years in the dark French cave until it was discovered in the early 20th century.

The artist’s hand signs are still clearly visible and the techniques used to render the face and mane details Objects like these clearly demonstrate that man used clay for artistic expression long before the actual firing of clay was discovered.

The walls of these caves also are covered with drawings of bison and other game animals, marked in carbon from the fires, as well as the earth minerals such as iron oxide and manganese, showing that these ceramic coloring materials that we still use today were known to our earliest ancestors.

The bisons’ shaggy mane and beard appear to be carved with a tool, but the jaws are traced by the sculptor’s fingernail.

The impression given is one of immense naturalistic beauty. The female bison is ready to mate, while the Bull is sniffing the air.

Both animals are supported by a central rock and are unbelievably well preserved (proving perhaps that there was never a passage connecting the Tuc d’Audoubert cave with the Trois Freres), although they have suffered some drying out, which has caused some cracks to appear across their bodies.

Also in the chamber are two other bison figures, both engraved on the ground.

Prehistorians have theorized that a small group of people (including a child) remained in the Tuc d’Audoubert cave with the sole reason of participating in certain ceremonies associated with cave art.

The remote location of the clay bison – beneath a low ceiling at the very end of the upper gallery, roughly 650 meters from the entrance, is consistent with their involvement in some type of ritualistic or shamanistic process.