A nearly 2,000-year-old phallic-shaped wooden object may have been used as a sexual tool by Britain’s ancient Romans, according to a new study.

The artifact was found in 1992 in a ditch at the Vindolanda Roman fort, near Hadrian’s Wall, which once marked the northwestern border of the Roman Empire in northern England. The researchers initially recorded the object as a mender, according to the study published Sunday in the academic journal Antiquity.

This misidentification was due to the tool being found alongside dozens of shoes and clothing accessories, and other small tools and craft waste products, according to a news release.

However, researchers have reinterpreted the artifact as a disembodied phallus and, examining it closely, have outlined some of its most likely possible functions.

Phallic Clues in Roman Art and Literature

According to the researchers, the carved object, 160 millimeters long, could have been used as a sexual tool, not necessarily for penetration, but rather for clitoral stimulation. If the archaeological find is indeed a sex toy, it represents the only known example of a “non-miniaturized” wooden phallus from Roman times, according to the study.

“It could very well be a sex object, and if it is, this is the earliest example from the Roman world,” Rob Collins, study co-author and Senior Lecturer in Archeology at Newcastle University, UK, told CNN.

“It shouldn’t surprise us. We know from Roman art and Roman literature that they used dildos, that they existed. But we haven’t found any archaeological examples yet,” he added.

According to the study, one of the reasons why these types of objects are not common in archaeological finds is that dildos used to be made of organic materials and are therefore unlikely to be preserved.

However, if the device is a sexual tool, it may not always be used exclusively as a sexual toy for pleasure.

According to the study, the object could have been used by a slaveholder against an enslaved person, whether male or female, to torture them or to assert their dominance, reinforcing power imbalances.

“The other thing we need to be aware of is that it would be easy to view this item as silly and frivolous and just for sexual gratification, but it could be a tool to perpetuate power imbalance and subjugation,” Collins said.

Other uses

According to the study, small, portable phallic objects were commonly found as pendants, probably to ward off evil or bad luck.

However, the object, carved from young ash roundwood, with a wide base and a narrow point, showed more wear at both ends than at the center. The fact that the object was smoother at the ends than in the center—probably due to oily skin and repeated gripping—suggests that those areas were the most in contact.

Thus, the phallus could have been embedded in a structure, statue, or other object, where it was touched by passersby to bring good luck or ward off misfortune. This ritual was common throughout the Roman Empire, according to the statement.

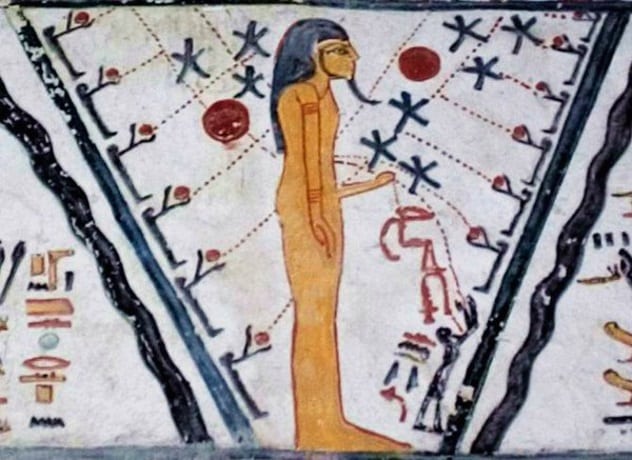

However, when the Roman phallus was compared with a wooden phallus from the New Kingdom of Egypt, it was found to lack some of the features one would expect it to have if mounted on a structure.

Another possible use for the object was as a mortar for grinding or mixing materials for cooking, cosmetics, ointments or medicines, according to the study. A phallus-shaped mortar could symbolically add protection or potency to what was brewed, and the act of grinding was the vehicle through which magic was believed to be activated, the researchers write.

According to Collins, the object could have served multiple purposes, or its function could have changed over time, and he said it was possible the object could have started out as a mortar, for example, before being used as a sexual object.

Finding similar examples in archeology could help researchers better identify the object’s function, said Collins, who hopes the study will prompt a review of objects currently in museum collections that might be similar to the phallus. wood, but have not been recognized as such.

“The wooden phallus may be the only one of its kind at this time, but it is unlikely that it was the only one of its kind used at the site, along the frontier, or indeed in Roman Britain.” added Barbara Birley, conservator of the Vindolanda Trust, in the statement.