Beginning ca. 481 B.C.E. to 403 B.C.E., the Warring States period was characterized by warfare as well as by its bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. Within the context of Chinese history, it followed the Spring and Autumn period and ended with the Qin wars of conquest that annexed all the other contender states, a situation that ultimately led to the victory of the Qin state in 221 B.C.E. thus consolidating the first unified Chinese empire known as the Qin dynasty.

Thus, the Qin dynasty consolidated as the first dynasty of Imperial China lasting from 221 to 206 B.C.E. This dynasty was founded by Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of Qin. During the mid and late third century B.C.E., the Qin state led a series of steady conquests resulting in the defeat of the powerless Zhou dynasty and eventually conquering the other six of the Seven Warring States. Although the Qin dynasty lasted only 15 years, the shortest major dynasty in Chinese history, and was ruled only by two emperors, it inaugurated an imperial system that lasted roughly from 221 B.C.E. until 1912 A.D. The goal of the Qin was to create a state unified by an structured and centralized political power and a large military supported by a stable economy. With these objectives, the Qin introduced several important reforms including a standardized currency, weights, measures, and a uniform system of writing, which aimed to unify the state and promote commerce. In spite of its short reign, the Qin dynasty greatly influenced the future of China, particularly the following Han dynasty, and it is thought that its name served as the origin of the European name for China.

A monumental, impressive and lasting artistic legacy of the Qin dynasty is the famous Terracotta Army, a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of emperor Qin Shi Huang. These sculptural group was a type of funerary art buried along with the emperor in 210–209 B.C.E. with the purpose of protecting him in his afterlife, a kind of microcosm representing the emperor’s imperial palace and entourage. This monumental ensemble was recently discovered in 1974 by local farmers in Lintong County (Xi’an, Shaanxi, China). The terracotta figures date from approximately the late third century B.C.E. and vary in height according to their roles, with the tallest being the generals. The figures also include warriors, chariots, horses, officials, acrobats, strongmen and musicians. It has been estimated that the three pits containing the Terracotta Army held more than 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses, and 150 cavalry horses, most of which still remain buried near Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum, and in total, the whole necropolis is thought to occupy and area of 98 square kilometers (38 square miles).

The terracotta figures are life-sized and vary in height, uniform, and hairstyle in accordance with their rank. Their faces appear to be different for each individual figure, but scholars have identified 10 basic face shapes. Originally, the figures were painted using ground precious stones: intensely fired bones (for white), iron oxide (dark red), cinnabar (red), malachite (green), azurite (blue), charcoal (black), a mix of cinnabar barium copper silicate (purple), tree sap extracted from the Chinese lacquer tree (brown), and various other colors including pink and lilac. The figures were manufactured in workshops by government laborers and local craftsmen using local materials. Heads, arms, legs, and torsos were created separately and then assembled together mirroring what we now know as an assembly line production, with specific parts manufactured and assembled after being fired, as opposed to crafting and firing individual pieces. When completed, the figures were placed in the pits in precise military formation according to rank and duty.

Kneeling archer, Terracotta Army (Museum of the Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shi Huang, Shaanxi).

The Qin bronze chariot number one, from a set of two found along with the Terracotta Army. The model is about half life size (Museum of the Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shi Huang, Shaanxi).

The Han, Wei and Tsi Dynasties

All the essential characteristics typically associated with Chinese art are featured in the artistic production of the Han period (2nd century B.C.E. – 220 A.D.). Portraiture was important, the sculpture focused in producing mostly bronze figurines featuring great dynamism in their attitudes, while on the walls of some burial chambers artists portrayed human silhouettes in crowded scenes or symbols such as those representing the cardinal points: the White Tiger of the West (Autumn), the Azure Dragon of the East (Spring), the Vermilion Bird of the South (Summer), the Black Tortoise or Black Warrior of the North (Winter), they all appeared engraved in flat relief on a dotted chiseled background. Pottery also experienced great developments and was covered with a plumbiferous* varnish and lacquered ornamentation. Some pieces made in jade are now considered masterpieces that show both an amazing technical mastery and the total conquest of a particular style (see for example the famous green horse of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London).

During the Han dynasty, bronze was used to make a wide range of vessels as well as weights, tallies, sculptures for tombs, lamps, censers, coins, mirrors, and other objects. The Han dynasty is divided into two eras: the Western Han, which lasted from 206 B.C.E. to A.D. 9, when the capital was at Xi’an, and the Eastern Han, which ruled from Luoyang between 25 and 220 A.D. Left: A Han bronze horse statuette with a lead saddle. Right: A gilded bronze oil lamp representing a kneeling female servant from ca. 2nd century B.C.E., its sliding shutter allowed for adjustments in the direction and brightness in light while it also trapped smoke within its body (Hebei Provincial Museum, Shijiazhuang).

The celebrated Gansu Flying Horse in bronze, ca. 25–220 A.D. (Gansu Provincial Museum). The statuette represents a galloping horse with one hoof resting softly on a flying swallow. This bronze is considered as a remarkable example of three-dimensional form and of animal portraiture with its head vividly expressing mettlesome vigor.

The Dahuting Tomb (Zhengzhou, Henan province, China), of the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 A.D.) was the burial place of Zhang Boya and his wife. It is famous for its well preserved murals and stone carvings. The tomb contains vault-arched burial chambers decorated with murals showing scenes of daily life. Depicted here is a detail of a mural representing a banquet scene.

Two door panels of a burial chamber carved in sandstone ca. 25-220 A.D., representing a lion (left) and a dragon (right) symbolizing west and east, it was found in the Sichuan Province, Xinjin region of China (Rietberg Museum, Zürich, Switzerland).

Examples of Han ceramics. Top Left: Western-Han painted ceramic jar garnished with raised reliefs of dragons, phoenixes, and taotie for the lug handles (Collection of Palace Museum, Beijing), ca. 206-208 B.C.E. Bottom Left: A Western-Han painted ceramic mounted cavalryman from the tomb of a military general (Western Han Dynasty, 206 B.C.E.- 8 A.D.) found at Xianyang, Shaanxi Province. The rider was depicted seated on a painted saddle, wearing a short robe and hemp shoes, with his hair bound up in a headdress; the sturdy and stout horse appears to be neighing. Center: A Han pottery female servant wearing silk robes, made in Terracotta, Western Han Period, ca. 206 B.C.E. – 9 A.D. (Cernuschi Museum, Paris). Top Right: A pottery dog found in a Han tomb wearing a decorative dog collar, indicating their domestication as a pet. Bottom Right: A Han dynasty pottery soldier with a faded coating of paint, his weapon is missing, Eastern Han dynasty, ca. 25-220 A.D. (Shanghai Museum).

The extraordinary Head and Partial Torso of a Horse from a jade figure (Han dynasty, 206 B.C.E. – 220 A.D.). This jade was found in a tomb alongside other objects buried with the body, since it was thought that the burial place became the home for the immortal soul. Jade was especially important in this process, due to its supposed magical powers to preserve the dead body (Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

Nothing is left from the architecture of the Han period except for the general layout of the monumental tombs, a model that was destined to be perpetuated throughout the history of China. This type of monumental tombs was preceded by the “road of the dead” lined with large zoomorphic sculptures. In China there are very few remains of ancient buildings. Nothing is left from the times of the Pantheon of Rome or of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and there are very few constructions contemporary to the cathedral of Burgos. However, from the study of the small models found in tombs it is possible to reconstruct the general appearance of the houses of that time: the walls were slightly widened at the base, with wide openings (like windows) supported either by pilasters or wood columns with footings, with tile-covered roofs decorated with finials in the shape of birds or other decorative animals. This is already the model of the typical Chinese house.

Examples of earthenware architecture models from the Han Dynasty. During the Han period, clay was also used to produce small un-glazed models of architectures and ordinary houses which were placed in tombs to accompany the dead. These models represent useful indicators of now lost mud and wood structures that would teach us about the architectural types during the Han dynasty. Many of these models also included pet animals and figurines of their occupants. Left: A Han dynasty votive house. Top Center: An architecture model from the Eastern Han Dynasty. Bottom Center: A pottery model of a palace found in a Han dynasty tomb. Right: A painted ceramic architectural model found in an Eastern-Han tomb at Jiazuo (Henan province). It depicts a fortified manor with towers, a courtyard, verandas, tiled rooftops, dougong* support brackets, and a covered bridge extending from the third floor of the main tower to the smaller watchtower. It also includes a dog laying in front the main door. The main building is 192 cm tall (Henan Provincial Museum, Zhengzhou, China).

When the Han dynasty fell in the year 220, the Empire plunged into anarchy and later, from the end of the fourth century and during two hundred years, China was split into two with the North dominated by foreign lineages (the Northern Wei who ruled the north of China from 386 to 534 A.D., and the Tsi who ruled beginning in the sixth century).

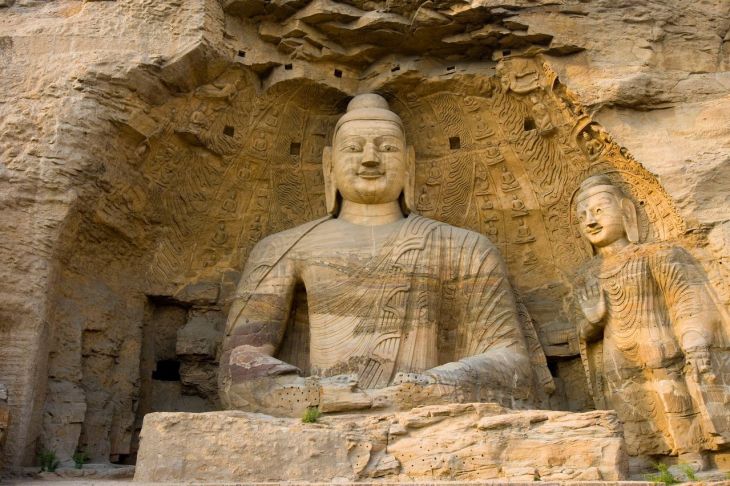

This was an intermediate period with profound historical consequences. The aristocracy and the old cultural traditions took then refuge in the South, where Taoism (with its inclination to mystical individualism) tended to replace the Confucian morality. Groups of scholars like that of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, who preferred to live in solitude meditating on philosophy or aesthetics, portray the prevailing restlessness of those times. These circumstances ended up favoring the spread of Buddhism already solidly introduced in the North. From the first century this new religion had spread from Gandhara and the State of the Kushana through the current Chinese Turkestan, an area that consequently became the focal point of Buddhist religious as well as artistic practices. These focal areas included the shrine of Bamyan (II-III centuries) important in the cultural connection between Persia, India and China, whose large open-air sculptures were inspired by the Greco-Buddhist’s of Gandhara and that in turn served as a model for the Chinese Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of another important focal area that included the numerous grottoes of Yungang (Shanxi) with their colossal rock Buddha carved during the time of the Northern Wei in the second half of the fifth century. Soon the Buddha iconography was adapted to the Chinese idiosyncrasy and the Hellenizing types derived from the school of Gandhara were followed by more slender representations with the bodies completely wrapped in the folds of their long and wide robes, with elongated faces and high cheekbones, almost closed eyelids, and lips insinuating a tender and mystical smile. This new Chinese iconography can be found since the late fifth century in the rock shrines of Longmen near Luoyang the new capital of the Wei.

The Shrine of Bamyan included two monumental statues of Buddha carved in the 6th century into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley (Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan). These statues represented the classic blended style of the Gandhara art period. The bodies of the statues were carved directly from the sandstone cliffs, but the faces and other details were modeled in mud mixed with straw and coated with stucco. This coating was in turned painted to enhance the expressions of the faces, hands, and folds of the robes. The statues were dynamited and destroyed in March 2001. Before being blown up in 2001 they were the largest examples of standing Buddha carvings in the world. The picture represents the Taller Buddha of Bamyan (also popularly known as “Solsol”) before 2001 which depicted Buddha Vairocana. It measured 53 mt tall inside a niche 58 mt tall. This Buddha dated probably from the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. and was painted carmine red.

The smaller Buddha statue of the Shrine of Bamyan (Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan) represented Sakyamuni Buddha and was known popularly as “Shahmama”. With a height of 35 mt inside a niche of 38 mt, it was built in 507 A.D. and destroyed in 2001. Originally, it was painted with multiple colors.

Above and below, Buddhas carved in the Grottoes of Yungang from the Northern Wei period, a group of ancient Chinese Buddhist temple grottoes near the city of Datong (province of Shanxi) and one of the three most famous ancient Buddhist sculptural sites of China (together with Longmen and Mogao). These grottoes represent an outstanding example of the Chinese stone carvings from the 5th and 6th centuries and occupy an area of 792 mt long and 9 to 18 mt high along the sandstone cliff. The shrine includes 53 major caves, along with 51,000 niches housing the same number of Buddha statues. Additionally, there are around 1,100 minor caves. The art found in these caves represents the fusion of Buddhist religious symbolic art from south and central Asia with Chinese cultural traditions.

Above and below, The Longmen Grottoes include some of the finest examples of Chinese Buddhist art. Housing tens of thousands of statues of Buddha and his disciples, they are located 12 km south of present-day Luoyang (Henan province, China). They include ca. 100,000 statues within the 2,345 caves and ranging from 25 mm to 17 m in height. The area also contains over 60 Buddhist pagodas and nearly 2,500 stelae and inscriptions, hence its name “Forest of Ancient Stelae”. The caves were dug along a 1 km stretch of cliff running along both banks of the river, 30% of them date from the Northern Wei and 60% from the Tang dynasty. In the pictures is depicted the Binyangzhongdong or the Middle Binyang Cave from the Northern Wei period carved on the west hill. It was built by Emperor Xuanwun to commemorate his father Xiaowen and his mother. It was created between 500-523 A.D. The central statue is of Sakyamuni Buddha with four images of Bodhisattvas flanking it. The roof was designed as a lotus flower. Some of the statues were sculpted with long features, thin faces, fishtail robes and traces of Greek influence resembling the Gandhara style.

In 581 Yan Jiang (Emperor Wen of Sui) the founder of the new Sui dynasty, reunited North and South China. This was a brilliant dynasty, especially during the reign of its second and last monarch the Emperor Yang Ying (Emperor Yang of Sui). More mundane than religious, the art of this period gave the figures of Buddha an air of solemn profanity manifested in the headdresses, tiaras and pendants of the Bodhisattvas which seem to evoke the luxury of Yang Ying’s court in Chang’an. After a period of revolts, this Sui dynasty was succeeded in the year 618 by the Tang dynasty founded by Li Guang from the House of Li, a dynasty that would last until the beginning of the 10th century.

Buddha images from the Sui dynasty. Left: A Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara* from 581-618 A.D. in limestone with traces of pigment (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Second from left: A stone statue of the Avalokitesvara Boddhisattva from 581-618 A.D. (Cernuschi Museum, Paris). Third from left: A stone figure of a Bodhisattva. Right: Bodhisattva from the late 6th century, in limestone with traces of pigment (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).