Much interesting information related to the chemicals used in the mummy making process to preserve corpse in ancient Egypt has come to light.Much interesting information related to the chemicals used in the mummy making process to preserve dead bodies in ancient Egypt has come to light. A new study has revealed that the chemicals used for mummification were brought from faraway countries. The Egyptians used a trade route for this which also passed through India.

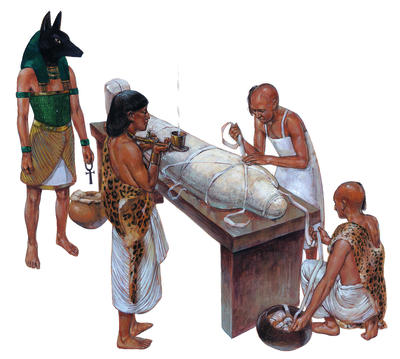

For ancient Egyptians, mummification was a spiritual process to give their loved ones adieu. According to the prehistoric texts, the process took about 70 days, with carefully defined rituals and invocations, to prepare the deceased for an eternal afterlife. People involved in the mummy-making procedure require specialized skills along with a long list of ingredients, and a professional class of embalmers guiding the rest with their religious and chemical knowledge.

Several old mummies continue to be found in Egypt, a famous site for archaeological discoveries. Now new research related to this has surfaced and it has exposed many secrets of mummification in ancient Egypt. Scientists have been able to figure out the materials that were used to preserve dead bodies from the dozens of beakers and bowls unearthed from an ancient mummification lab. The even bigger discovery is that some of these materials were imported from Asian countries like India, Lebanon, and others.

Earlier in 2016, an extraordinary collection of 31 ancient Chinese pottery vessels were found at the bottom of a 42-foot-deep well in the Saqqara Necropolis, located in the South of the capital- Cairo. Discovered utensils and beakers belong to the 664-525 BC, from which great information has now come to the fore. Researchers studied these utensils for years and came across much startling information from 664-525 BC.

According to a report by the news agency AFP, scientists found traces of resins (adhesive substances) obtained from Asian trees, cedar oil from Lebanon, and bitumen found in the Dead Sea inside the pots. This also sheds light on the fact that global trade was flourishing during that time.

Ancient Egyptians used to apply a type of paste on the dead bodies, which was miraculous enough to preserve the mortal remains. The process is called mummification. The embalmers believed that if the dead bodies are kept intact in every way possible, then they reach the next life.

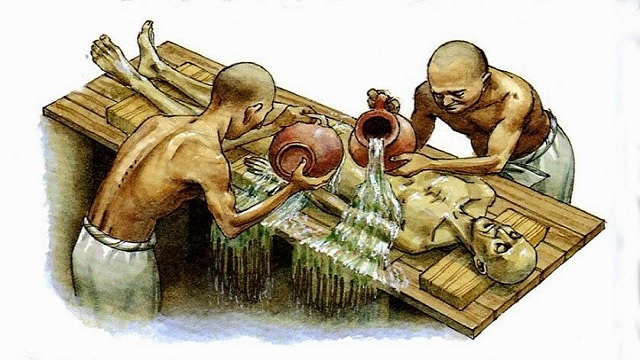

Researchers tried to replicate the mummy making process in the lab, and it took about 70 days. During this time, the experts dried the dead body by covering it with natron salt. Then, they removed its entrails- lungs, stomach, intestines, and liver. The brain was also taken out.

After the drying and removal were over, the embalmers washed the dead body and applied a paste of various substances to prevent it from rotting in the presence of priests.

However, scientists are not sure about the ancient Egyptians’ process of mummification. Their way could be different, but the procedure that the experts enacted in the modern lab were based on the information discovered.

Philipp Stockhammer, an archaeologist at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, said that there is almost no textual evidence of how this worked how the substances were mixed, and how they were named.

In a study published in Nature this week, Stockhammer and his colleagues mentioned that by identifying residues from labeled jars found in an ancient Egyptian mummification workshop, the researchers were able to reenact the process involving complex chemistry and exotic ingredients. The major ingredient was resins sourced from a continent away, the archaeologist claimed.

“You can actually look into the vessels and see what’s still inside,” says Barbara Huber, an archaeological scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology who was not involved with the research.

University of Tübingen archaeologist Ramadan Hussein, who died in the spring of 2022, identified shallow aboveground pits where the procedure took place. He and his team found a partway down a nearby shaft that lead to an underground chamber outfitted with flat stone niches for corpses- a workshop for mummifiers. “It’s the first physical evidence for the places where they worked,” says University of York archaeo-chemist Stephen Buckley. They also found burial chambers almost 30 meters down the shaft.

The shaft was very carefully filled with sand, rocks—and dozens of embalming vessels that seemed to have been ritually disposed of after workers had used them. “They turned it into a hiding place for the tools,” Hussein said in an interview before his death. “We found cups, bowls, plates, and incense burners inscribed with the names of oils and substances used for embalming.”

The analysis done on the residues found in the empty vessels revealed traces of animal fats, beeswax, vegetable oils, and bitumen along with multiple plant resins- ingredients that were probably mixed and heated to form the paste. Being made of natural substances, it was easier to identify the properties recovered from the pottery vessels, even after thousands of years.

“The more fatty and sticky a residue is, the better results you get,” Stockhammer says. “We had good organic preservation, and we had residues that preserve well,” he added.

After immersing the corpses in natron, they were treated with the sticky mixture to seal the skin. It blocked the decay and decomposition by bacteria. Stockhammer said that the materials they found have an antibacterial function. He defined this part of the procedure as the most “complicated,” as it is where the chemistry begins. While some of the paste may have been applied directly to the corpses, others were probably applied to the linen bandages dipped directly into wide-mouthed “goldfish bowl” vessels.

Some of the bowls still had stains on the outside from spills and dripping mummy wrappings. According to Hubber, some of the containers were labeled naming specific ingredients- antiu or sefet. Some also had more general descriptions like “to make his odor pleasant” and “treatment of the head.” “For the first time, you have a direct correlation between text and a specific residue,” Huber says. “I don’t know if there’s a better case study than having them all together.”

It is to be noted that the word antiu appears thousands of times in ancient Egyptian texts, and for more than a century Egyptologists thought it referred to myrrh- the resin of a particular thorn tree. However, the vessels labeled antiu at the mummification workshop contained other substances, most profoundly cedar.

Apart from that, researchers also identified more exotic ingredients, including dammar and elemi, resins extracted from hardwoods native to Southeast Asian rainforests thousands of kilometers from ancient Egypt. Meanwhile, cedar and pistachio were known to have been sourced from around the Mediterranean, and pitch from the Dead Sea. “Mummification drove globalization,” said Stockhammer.