The remains of a 5,000year-old man discovered in a mass burial in northern Chile have been identified as those of a Neolithic fisherman who drowned. A comprehensive investigation of the man’s bones revealed data about his life, including telltale evidence of his lifestyle and cause of death.

The findings of an investigation of the man’s remains discovered near the Atacama Desert have just been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Scientists from Chile, Australia, and the United Kingdom were among the interdisciplinary team of experts responsible for the analysis. Their work has paved the way for forensic archaeology by providing a wealth of information about someone who lived and died in the prehistoric age.

The Difficult Life and Tragic End of a Neolithic Fisherman

The skeleton of the unfortunate man was discovered along Chile’s coast in the Copa district, which is next to the Atacama Desert. He was one of four people discovered in the mass grave, along with one other man, one lady, and a child.

According to main study author Pedro Andrade, an archaeologist, and anthropologist at the University of Concepción in Chile, “what we can deduce from similar settings is that they probably belonged to the same familial group.” Andrade explained that the persons in the burial hadn’t all died at the same time, but had been buried separately over nearly a century.

When he died, the drowning victim was around 5 feet, 3 inches (1.6 meters) tall, and between the ages of 35 and 45. The man had lived a tough life, based on the state of his skeleton. His remains revealed symptoms of degenerative disease and physical suffering, such as osteoarthritis in his back and elbows, as well as injuries associated with a blunt head blow.

Because he had periodontal disease and oral abscesses, this Neolithic fisherman’s teeth were in bad shape. The state of his eye sockets revealed he’d had an iron deficit caused by a marine animal parasite that had found its way into his system. Marks imprinted on locations where muscles were once joined on his legs and arms suggested he’d done repetitive movements likely related to fishing. To gather shellfish, this would have entailed rowing, harpooning, and sitting.

If the inhaled water originates from the sea, it will almost certainly be polluted with diatoms, a minute form of algae that will be discovered all over the drowned person’s body. Naturally, most of the evidence of how a drowned invidual died would be lost as their corpse decayed over time. However, even after everything else has died, traces of diatoms will persist in the bone marrow.

The scientists who worked on this project weren’t sure if the diatom detection method would work on a skeleton that had been buried for 5,000 years. They decided to change the testing techniques to improve their chances of success.

Testing Procedures for the Analysis of Ancient Remains are being fine-tuned.

While the contemporary diatom test is effective in detecting microscopic diatoms, it also tends to kill other small creatures and particles that may be present in the bone marrow. To avoid causing such harm to their ancient remains, the researchers devised a “less aggressive technique” that maintained a larger spectrum of organic material from the preserved bone marrow they retrieved.

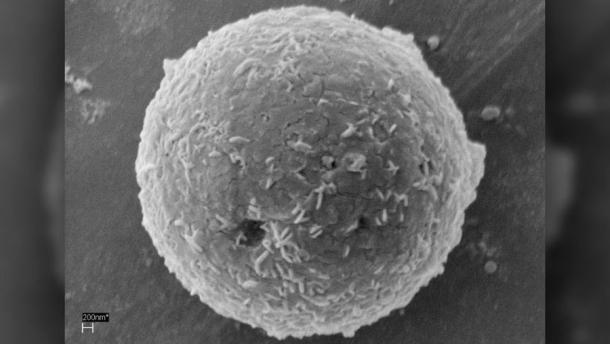

The scientists were ecstatic to discover that the retrieved bone marrow was teeming with the preserved remains of small ocean life when they examined it with a scanning electron microscope. They discovered algae, parasite eggs, and tiny sponge-like structures known as spicules among their findings.

“We know he drowned in shallow saltwater because of what we found in his bone marrow,” research co-author and University of Southampton earth sciences professor James Goff said in a University of Southampton press statement. “We could see that the poor man consumed sediment in his final moments because sediment does not float around in adequate amounts in deeper waters,” said the investigator.

The researchers investigated the likelihood that the man died in a tsunami that surged far enough inland to cause widespread damage and kill a large number of people. Other research has shown that Chile was hit by more than one powerful tsunami around 5,000 years ago, so this is a distinct possibility.

However, the experts feel it is more plausible that he fell off a boat or raft while out at sea fishing and was unable to return to his boat or land safely. The man’s rib bones were broken, and he was missing both cervical vertebrae and shoulder joints, all of which occurred after he drowned and his body was washed back to shore and slammed into rocks.

Did a lot of people drown in prehistoric times? Researchers may find out soon.

The scholars engaged in this remarkable work have advanced the science of prehistoric forensic archaeology by their meticulous methods in examining the Neolithic fisherman. Their method could be used on other skeletons discovered in coastal burial sites.

“We’ve cracked open a whole new method of doing things by spending more time on the forensic technique and checking for a broader range of beasties inside the archaic bones,” Professor Goff stated. “This can help us learn a lot more about how difficult it was to live on the coast in prehistoric times—and how people there, like us, were affected by catastrophic catastrophes.”

Many mass graves have been discovered in coastal locations around the world. Researchers will be able to examine retrieved skeletal remains for evidence of drowning, which might show past tsunamis that drowned many people or isolated instances that drowned only a few people.