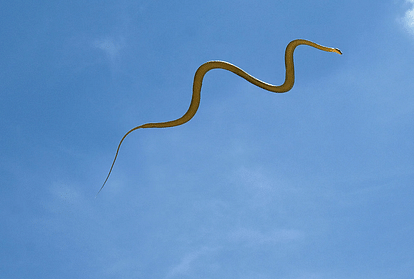

Add flying snakes to the ever-growing list of insects and reptiles getting their time in the spotlight during a year in which people are probably looking into online zoology courses.

A recent study published in the journal Nature Physics sheds light on why the paradise tree snake (C. paradisi) undulates in midair. The motion keeps the snake — which doesn’t actually fly, it just glides — stable after jumping from trees, researchers at Virginia Tech found.

But, for years, it was unknown if the motion served any purpose, said Isaac Yeaton, the study’s lead researcher and a scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

“The most striking feature of when (the snakes) are gliding is the undulation,” said Yeaton, who conducted the research while he was a Ph. D. student in mechanical engineering at Virginia Tech.

To capture more detail, the researchers conducted their study inside “The Cube,” a four-story black-box theater on Virginia Tech’s campus. The theater is equipped with motion-capture cameras, and 11 to 17 markers were placed on the snakes, which allowed the researchers to record “the exact position of the snake’s body more than 300 times per glide.” Each glide took about two seconds.

The team collected data over May and June in 2015, Yeaton said. The group spent two years analyzing the data, then submitted its paper in fall 2018, he said.

Toxic toads:Florida tells residents to humanely kill these invasive, toxic toads that are lethal to pets

“When we did the work, we were basically able to get our first full understanding of what the animal is doing in the air and then that really led us to build this complete model of the snake’s dynamics,” Yeaton said. “We could then start asking those questions, ‘Why is the snake undulating? What effect does it have?’”

Researchers found the snakes moved from side to side, but also slightly up and down. They were able to generate a computer physics model of the snake to better study the undulations and their impact on the snake’s glide.

“You can do things with the model that you can’t do with the live animal,” Virginia Tech professor Jake Socha said. “What we wanted to do with the live animal is tell it to stop undulating. Like, ‘Hey, snake, stop undulating.’ We could tell the model to do that. When you turned the undulation off in the model, you see that you get really bad gliding performance.

He added, “In fact, it tumbles out of the sky much more readily than when you have undulation.”

No need to worry, for now, about the snakes showing up stateside like “murder hornets” and gypsy moths — they’re native to south and southeast Asia.

The reason behind the snakes’ undulation was a riddle begging to be solved, said Socha, who has been studying flying snakes since 1996. The discovery could be applied to future robotics, the researchers found.

“It’s pretty interesting because all other animal gliders — and I think most engineered gliders, as well — the thing they all share is they pretty much hold still,” Socha said. “You might make small adjustments, but you’re holding still in your gliding.”

All snakes undulate when they move, so snakes might have just been mimicking their motion on the ground while in the air, he said.

Asian giant ‘murder’ hornet:5 things to know about the invasive species

“If you jump off a big cliff and you start flailing your arms, that doesn’t really do anything,” Socha said with a laugh. “But you do it. The same thing is there, where the undulation is something that all snakes do when they’re trying to locomote.”

“The Cube” was originally built for performing arts students, Socha said. Part of the process of getting to use the building was ensuring the snakes wouldn’t wander off and end up in some unsuspecting professor’s office, he added.

“I guarantee you they did not have flying snakes in mind when they designed this facility,” Socha said.