In prehistoric times, winged reptiles soared high above the dinosaurs. Like birds, they laid eggs, gathered food and fed their flightless offspring. For most of history, we didn’t know much about their eggs, or the babies inside them, because paleontologists had found only eight eggs that weren’t completely flattened.

But now, thanks to a deposit found in China, paleontologists have hundreds to study. Research about the find was published in the journal Science.

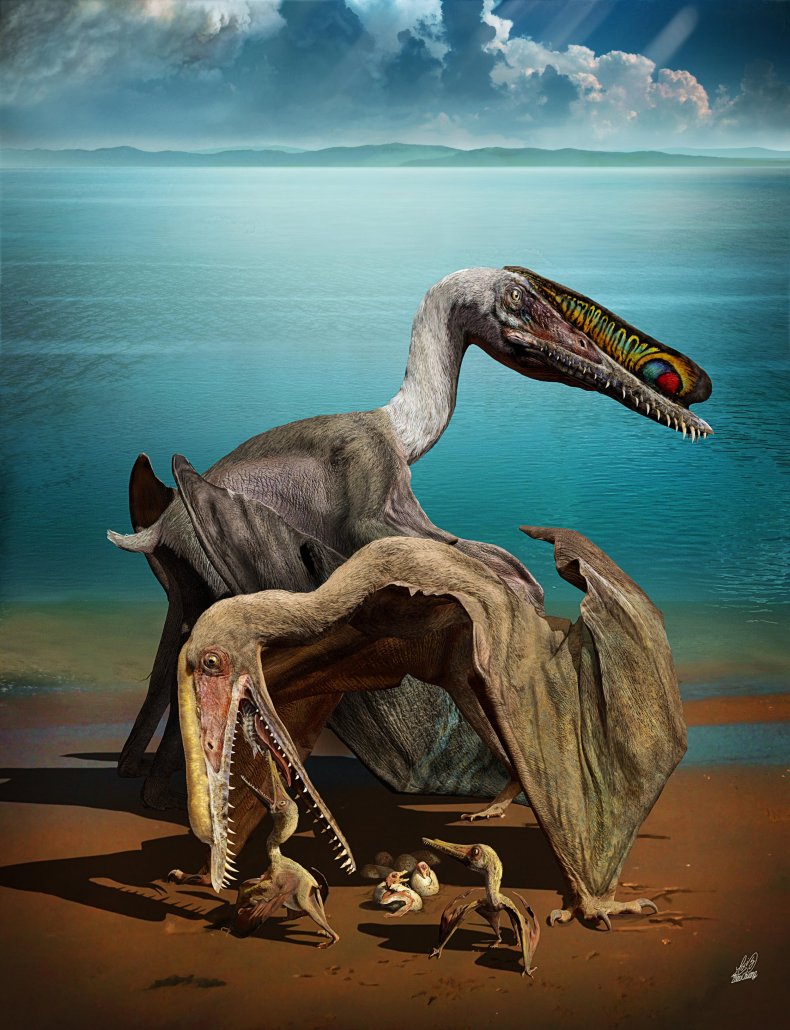

An illustration of the pterosaurs Hamipterus tianshanensis, showing sexual dimorphism between the male, top, and the female, bottom.

Due to a weather-related event in the early Cretaceous, dozens of bones and hundreds of eggs of the same species were collected at the same spot in China. The spot is a veritable Eden of pterosaurs.

With adult skeletons and at least 215 eggs recovered at the site, paleontologists are just beginning to uncover new knowledge about these flying beasts of the sky. So far, the paleontologists have discovered that 16 of the eggs had the remains of embryos within them.

These animals belong to the dinosaur-like winged creatures called “pterosaurs.” Pterodactyl is most famous pterosaur, but it’s a diverse group, including animals from the size of seagulls to the size of small planes. The deposit found in China includes only one species, and that is a particularly odd species, Hamipterus tianshanensis.

Unlike modern birds, many pterosaurs, like H. tianshanensis, had lots of sharp teeth. They were also “sexually dimorphic,” like many birds, meaning that the males and females looked different. The males had notable protrusions on their noses, possibly to help attract females.

The scientists don’t believe that the site they recovered was a nest because the eggs were scattered around randomly, unlike the careful nests that dinosaurs and birds keep. Furthermore, the eggs were a wide variety of sizes, indicating that they had been laid at different times by different animals. Unfortunately, that means that they don’t know how many eggs each female would lay per clutch, nor how they were organized. They suspect that a flood of some sort washed the eggs downstream to a spot where they all rolled to a stop.

By examining the embryonic remains from the pterosaurs, the paleontologists were able to better understand the early life of these flying creatures.

“We learned a lot,” Alexander Kellner, a paleontologist with Laboratório de Sistemática e Tafonomia de Vertebrados Fósseis, told Newsweek. “For example, the bones associated with wings were less developed compared to the embryos development with their legs. So what we could learn from that? That most pterosaurs, when they hatched, they could walk, but they could not fly, so most likely they needed some parental care.”

While this deposit gives paleontologists a lot to work with, they note that there could be even more. They have counted 215 visible eggs, but they say that more eggs buried beneath them could bring the total to 300. Perhaps there are even more nearby. They scientists didn’t have time to examine every egg. They had opened only 40 to find out if there were embryonic remains inside, and Kellner said CT scans are only somewhat useful.

“We want to find more eggs to make a much more detailed picture of embryonic development,” Kellner said. “So we are quite excited about that…. I’m quite certainly sure that there must be more embryos there.”